Shivakantjha.org - Triplet 21 - General Assessment of 'Direct Taxes Code Bill'

Triplet 22

General Assessment of 'Direct Taxes Code Bill'

By Shiva Kant Jha

September 4, 2009

LET us

explore about (i) the persons who drew up this Direct Taxes Code Bill 2009,

and let us think about (ii) the objectives for which solutions were sought

by them. These issues are organically linked with the health of our Civil

Services, and our attitudes towards the ways of the schemers who, as per

the Shah Commission Report, constitute "The Root of All Evil".

I would come to the state of the health of the Civil Services, and the agenda

of the operators through dense fog in the three leaves of the next Triplet.

(i)

Silhouettes of authors of said Code Bill stand completely shrouded

We do not know who authored the said Code. Its Foreword has been written by Shri Pranab Mukherjee, the Finance Minister. Few can believe that he could have gone through the provisions of this Code.

Let

us see how the draft of the Income-tax Act, 1961 was drawn up. The Committee

(consisting of P. Satyanarayan Rao, G.N. Joshi, N.A. Palkhivala,

under the Chairmanship of M.C. Setalvad) drafted the 12 th Report of the

First Law Commission (1958) whereon [with certain borrowings from the Direct

Taxes Administration Enquiry Committee Report (1959)] the Income-tax Act,

1961 was based, and enacted. Their Reports were comprehensive enough to give

us full ideas of the problems which Commission and the Committee dealt with.

They provided masterly analysis of problems, and articulated their recommendations

amply setting out their reasons for their criticism and suggestions. We knew

that their authors were great masters of jurisprudence, possessed internationally

recognized professional caliber, and integrity, and had wisdom and sagacity

rarely noticed these days. We can appreciate the said Code Bill only on knowing

who drew it up and after what sort of enquiry and deliberation. Para 1.7

of the Introduction to the discussion draft says "... In

drafting the code, the Central Board of Direct Taxes (the Board) has, to

the extent possible, started on a clean slate ." Not even

with the cockroach's brain one can ever believe this statement true. I do

not wish to enter into a debate about the superiority or otherwise of our

brain with that that of the cockroach at this moment. One should ascertain

the veracity of this contention by seeking information under the RTI Act.

At best, if at all the CBDT drafted this Code with such pronounced death

wish, it must have been under some extrinsic pressure such as that which

had worked on it to get the infamous Circular issued (which was quashed by

the Delhi High Court in Shiva Kant Jha v. Union of India ). The

nation demands an answer. Even the CBDT should come clean by making its position

clear to people.

Even

the silhouettes of the authors of the said Code stand completely shrouded.

There are good reasons to speculate. Did our Government outsource the drawing

up of the said Code to some agency, Indian or foreign, which needs to be

kept hidden for reasons not far to seek despite the opaque system which has

begotten it. We know how great Codes were drafted in the past. Their draft

was preceded by thorough research conducted by eminent experts who kept their

deliberative process transparent and accessible to all. The Government must

not give an impression that things are being engineered through stealth for

ulterior purposes. Milton 's Comus aptly said: ''T is only daylight that

makes sin." Shah Commission of Enquiry ( Third and Final Report

p. 231) said

precisely the same: "It has been established that more the effort at

secrecy the greater the chances of abuse of authority by the functionaries".

But the most telling statement was by our great Sankaracharya who said in Aparoksanubhuti:

notpadyate vina jnanam vicarena nyasadhanaih

yatha padarthabhanam hi prakasena vina kvacit

(Without inquiry, wisdom cannot be attained by any other means.)

We

trust that our distinguished experts occupying high government posts would

enlighten us with ideas with their utmost good faith. But our faith stands

shaken by our experience. It is in the public domain that the Report of the

technical expert group headed by Mashelkar on 'the TRIPS compatibility' of

our patent laws was tainted with plagiarism. When gross plagiarism was found

in his Intellectual Property and Competitive Strategies in the 21st Century,

he is said to have said: "I was working on so many things at the time that

I took the help of researchers to add new information to what I had written,…Unfortunately,

they copied verbatim from somebody else's writings. I know it is a sin. But

I was so pressed for time that this skipped my attention."

I

think I am not much off the mark if I try to read something from certain

expressions in this Code Bill. The constraints of space do not permit me

to go deep and wide to explore who might have fathered it. Only one expression

I am taking up. At page A-37 of the said Code (as published by the Department

of Revenue), something is stated under the green caption "Area based

exemptions grandfathered". It says:

"… Hence,

the Code does not allow area-based exemptions. Area-based exemptions that

are available under the Income Tax Act, 1961 will be grandfathered."

'Grandfathered'

would mean 'eliminated' or dispensed with. The expression 'grandfather'

as a verb transitive is seldom used in cultured society. 'Grandfather' is

the father of one's mother or father. In verbal sense it means 'to exempt

(one involved in an activity or business) from new regulations'. Obviously

the draftsmen have not used this word in that sense. One wonders how an Indian

can think of 'grandfather' as a synonym for 'elimination'. Does it suggest

that the grandfathers deserve to be eliminated? Does it promote the WTO agenda

in which the humans are trading wares, and the grandfathers, not being market-friendly,

deserve to be eliminated in the present roaring Pax Mercatus fathered

by the neo-liberal paradigm? It is an insult to senior citizens. How could

Mr. Mukherjee, a septuagenarian himself, miss this grotesquely disturbing

distortion of this word with which none is supposed to be unfamiliar whatever

be their personal experience in relationship with father or grandfather.

Can any Indian write this way?

'Clean slate' theory

The

explanatory comments circulated with the Direct Taxes Code Bill makes an

amazing statement. It says: ".... In drafting the code,

the Central Board of Direct Taxes (the Board) has, to the extent possible,

started on a clean slate ." Only an ignoramus can ever

pretend to draft a Code on a clean slate. No society writes its script of

growth, or decay, on a clean slate; no law is ever framed on a clean slate,

none in senses can ever set out on a clean slate. The past is bred in one's

marrow itself. This sort of plea is spacious plea merely to make what is

improper ex facie acceptable by the people. Our Constitution is the current

product of our long constitutional history, as is our culture of our long

and glorious history. Hence we are driven to view this contention with contempt

it instantly deserves. George Meredith said in Modern Love: ''We

are betrayed by what is false within." And let us say in Tennyson's

beauteous words: "Ring out the false, ring in the true". Let us

ring in the true.

(ii) This Management by Objective (the MBO)

Shri Pranab Mukherjee draws up the objective of this Direct Taxes Code Bill 2009 in these words:

"The thrust of the Code is to improve the efficiency and equity of our tax system by eliminating distortions in the tax structure, introducing moderate levels of taxation and expanding the tax base. The attempt is to simplify the language to enable better comprehension and remove ambiguity to foster voluntary compliance. The new Code is designed to provide stability in the tax regime as it is based on well accepted principles of taxation and best international practice…."

We can compare it with the description of task that the First Law Commission had set for itself while on its assignment to redraw the income-tax law. In the Introduction to the 12th Report, the First Law Commission said:

"There is hardly any Act on the Indian Statute Book which is so complicated, so illogical in its arrangement, and in some respects so obscure as the Indian Income-Tax Act, 1922. Courts and commentators have commented on the illogical arrangement of the provisions of the Act. It has been repeatedly pointed out that the amendments made from time to time to the Act, directed as they frequently are at stopping an exit through the net of taxation freshly disclosed,

are too often framed without sufficient regard to the basic scheme upon which the Act was originally rested. Provisions dealing with the same topic or subject-matter are scattered through the various Chapters of the Act, and only a thorough knowledge of the whole Act would enable any one to find out all the provisions bearing on a certain point. Added to the illogicality of the arrangement are two other defects, inaccuracy in the use of language and a degree of obscurity which make it difficult to have a glimpse of the

real intention of the legislature. As Lord Wrenbury said (with reference to the corresponding Act of the United Kingdom), "No reliance can be placed upon an assumption of accuracy in the use of language in these Acts". Rex v. Kensington Income-tax Commissioner, 6 T. C. 613, 623 (H.L.)

The hopeless confusion into which the Income-tax law has fallen is mainly due to precipitate and continuous tinkering with the Act by the legislature. The amendments to the Income-tax Act have been so short-sighted and so short-lived as to rob the law of that modicum of stability which is essential to its healthy growth. Before the provisions of the Act can be sufficiently clarified by the judicial process, new provisions are substituted in their place. In legislation as in other fields of human activity, it is well to bear in mind the dictum of Bacon, "Tarry a little, so that we may make an end the sooner." Stability is most essential to the proper administration of a taxing statute, and if the tax structure of this country is to be put on a sound footing, it is essential that a halt should be called to the making

of ill-digested amendments in a frenzy of hurry which has characterized the history of income-tax law of the last few years. '

The Law Commission did a remarkably good work, and achieved some of its objectives with commendable excellence. I do not intend to hold an inquest on this Direct Taxes Code Bill till the provisions are critically analysed and implications comprehended. But an overview of the said Code shows poor articulation of the objectives, and deficient comprehension of the fiscal jurisprudence. Adopting John Bright's saying it can be said: "that the trouble with great thinkers [ as advertised] is that they usually think wrong" and the trouble with realistic appraisal is that it usually lacks in reality. Yet I hope our experts would examine the worth of the provisions of the said Code without putting themselves under the blinkers of vested interests. Common men, fighting how to keep the wolf away from the door, have neither time, nor acumen, nor energy to wade through this tom of words written in English which most of them do not know. And going by past experience we cannot be sure that the Code Bill would be enacted after having been read, much less understood. We live in the phase of arrogant and expansive Executive, declining and credulous Parliament, formalistic judiciary, indifferent public opinion, and low arousal citizenry. So the responsibility of those who know is great as knowledge is under trust held pro bono publico .

(iii) Tragedy of Waste

I agree that certain changes in the income tax law are called for. But the profile of changes emerging from the said Code does not inspire confidence. This new Code would put an enormous burden both on the tax gatherers and tax payers. We should be very circumspect in casting avoidable burden on them as they already groan under the heat and burden of rough existence. The process to learn, unlearn, and re-learn this species of law is a tragedy of waste. We must be certain how the calculus of burdens and benefits would work. We owe this duty to the nation. Hurry is no good in matter as momentous as the repeal of the Income-tax Act, 1961, and adoption of this new Code.

(iv) This short shrift to Parliament

The

tax rates are proposed to be made in the said Code thus dispensing with the

requirement of prescribing them in the annual Finance Acts. In Maharajah

of Pithapuram v. CIT (13

ITR 221, 223-24) the Privy Council observed: the Income tax Act "has no

operative effect except so far as it is rendered applicable for the recovery

of tax imposed for a particular fiscal year by the Finance Act." The annual

Finance Act is not moved as a mere historical formality to stress on the fact

that the imposition of income-tax is just a temporary affair. In fact, it is

an integral part of the mechanism of the constitutional control of the Executive. The

New Encyclopedia Britannica aptly observes:

"The limits to the right of the public authority to impose taxes are set by the power that is qualified to do so under constitutional law. …..

The historical origins of this principle are identical with those of

political liberty and representative government – the right of the citizens. " (Italics

supplied)

It is a fundamental principle of our Constitutional jurisprudence that every year the Executive Government must beg before Parliament for an authorization to levy taxes at certain rates. For historical reasons it applies mainly to the Direct Taxes. The German Chancellor Bismarck destroyed democracy in Germany by dispensing with Parliament as he had obtained a perpetual authority to levy taxation from the German Parliament (Diet). This line of thinking leads me to suggest that the present system of tax rates fixation through the Finance Acts deserve continuance. It is a constitutional principle of highest importance that neither we can be taxed through an executive fiat, nor untaxed through an executive concession. To tax or grant exemption form tax are the two facets of the same thing. It was aptly stated by the Rajasthan High Court in H.R.& G. Industries v. State of Rajasthan ( A I R 1964 Raj. 205 at 213) :

"It

is well established that the power to exempt from tax is a sovereign

power and no State can fetter its own much less the future legislative

authority of its successor. See Associated Stone Industries Kotah v.

Union of India ILR (1958) 8 Raj 700 and Maharaja Shree Umed Mills Ltd

v. Union of India ILR (1959) 9 Raj. 984"

(v) Even a statute can be drafted in plain English

One of the aims of this Code is 'to simplify the language to enable better comprehension and remove ambiguity to foster voluntary compliance' No doubt these are good objectives. But the achievement, as this Code evidences, is dismal. Not to say about the substantive provision, even its interpretation sections are couched in involved language. Interpretation clauses need interpretation to become intelligible. The dictionary of definitions include words which even the morons understand, but it also has a rich crop of definitions which themselves need definitions. Readers get flabbergasted by the semantic and verbal confusion worse compounded by syntactic laxity. While going through the raas lila of the 'negative' and 'positive variants, one feels one needs a degree in econometrics. Can't all this could have been written in plain English? To run down the present Act of 1961 on the count of ambiguity is misconceived. 'A word or phrase is ambiguous when it has more than one meaning. …..in construing a …statute the Court has to ascertain the intention of "them that made it" That intention is to be gathered from the words used, and normally if the words bear a plain ordinary meaning that meaning gives effect to the intention ….But the plain ordinary meaning of words may be qualified by the circumstances with reference to which the words are used, so that the intention is better effectuated by giving to the words a different meaning from that which they normally bear' [M. M. Seervai]. Some guidance in the ascertainment of meaning is expected from the Notes on the Clauses. But we find them mostly of no use. See in what way we are enlightened by the explanatory provision of Section 258 (8) of this Direct Taxes Code. It repeats the provision itself, and does nothing more. It is essential to rid this Code Bill of its gobbledygook, jargons and linguistic distortions of several sorts. If the law fails in giving unclear clarion call how can the tax-gatherers and tax-payers discharge their duty? We hope a relook on the Code would be given by the competent persons before it is imposed on the nation. Let not the remissness of moments punish us for decades of litigious odyssey through the ITAT and court.

(vi)

Wider and deeper deliberations are needed

Taxation

in our welfare State is not a mere instrument to rake in revenue for the

Government (as it was during Akbar's regime when Raja Todar Mal was the Emperor's

Finance Minister). Through the Direct Taxes law much is being done for economic

development in certain select areas of our country, and also for the economic

and commercial benefits to segments which need them on the grounds of public

policy. This Direct Taxes Code 'grandfathers' (dispenses with) them. We do

not know whether the proposed changes have been discussed with their stakeholders.

This Code would have been released along with a comprehensive Report highlighting

(i) the expectations and achievements of the provisions as they stand, and

why the provisions call for elimination; (ii) the nature and outcome of the

deliberations which have warranted such changes. We are fed up with the 'assumptions'

of this sort or that, and ex cathedra statements by experts this or that.

(vii) Appeals to the National Tax Tribunal

Section

192 of the Direct Taxes Code Bill contemplates the setting up of NTT.

The explanatory comment going with the said Code says (para 21.2): "Once

the NTT is established, it will exercise the powers of the High Court." This

idea is atrociously wrong. Enacted soon, it will be struck down as unconstitutional.

High Court's Judicial Review Power cannot be exercised by a tribunal, whether

statutory (as this proposed) or constitutional as is the CAT. Besides, the

reach of the Judicial Review is so wide that any good advocate can turn most

of the normal appeal cases into Writ Cases under Art. 226 of the Constitution

of India. I had written two articles touching this topic [they are: 'National

Tax Tribunal will do no good' and 'Mr Singh, instead of Tax Tribunal let's

strengthen ITAT. They are at www.taxindiaonline.co and

also on my website www.shivakantjha.org .

It is enough for the present.

(viii) Send the draft Code to Law Commission

It is submitted that it would be prudent to refer the Direct Taxes Code to the Law Commission of India, or to an expert committee consisting of experts with established professional reputation. The members of public be heard by that Commission. There should be total transparency if the quest for solutions is right and proper. The Report to be drawn up should be in a protocol as comprehensive as the 12 th Report of the First Law Commission so that people can comprehend the reasons for the proposed changes, and can evaluate the recommendations.

(viii) Conclusion

We

all know the oft-quoted prudent lines of Tennyson in 'the Passing of Arthur': "The

old order changeth, yielding place to new'. But it is prudent to keep in

mind what Robert Browning said in By the Fire-side:

When earth breaks up and heaven expands,

How will the change strike me and you

ln the house not made with hands?

We

must know the 'hands' that shaped the Code, and its provisions which "strike

me and you".

II

This Stratagen to bruise, batter and bargain CBDT and IRS

Raison d'être of the CBDT

The CBDT was established by the Central Board of Revenue Act, 1963 framed in the light of the Direct Taxes Administration Enquiry Committee, and the Central Excise Reorganisation Committee. The 'Statement of Objects and Reasons' of the Act stated its objective thus:

"Owing to the very considerable expansion of the Union revenue administration since 1924, substantial strengthening of the Board of Revenue at the Centre as well as its functional bifurcation has become a matter of urgent necessity."

The Central Board of Revenue Act, 1963 established separate Central Boards for Direct Taxes and for Excise and Customs. The Section 3 of the said Act prescribes:

" …..each

such Board shall, subject to the control of the Central Government, exercise

such powers and perform such duties, as may be entrusted to that Board

by the Central Government or by or under any law."

Section 4 authorizes the Central Government to "make rules for the purpose of regulating the transaction of business by each Board", and such a rule "shall be laid as soon as may be after it is made before each House of Parliament while it is in session for a total period of thirty days which may be comprised in one session or in two successive sessions". The following two important propositions inevitably follow:

(i)

Each such Board "shall, subject to the control of the Central Government,

exercise such powers and perform such duties, as may be entrusted to that

Board by the Central Government"; and

(ii) Each such Board shall exercise such powers and perform such duties, as may be entrusted to that Board by the Central Government by or under any law.

Apropos

(ii) supra: In effect, for exercising the functions entrusted to such Boards

by the respective Acts, the Boards are not "subject to the control of

the Central Government". They discharge the Parliamentary commission

granted by the statutes to collect revenue as per the law; and they are accountable

only to the Courts on the points of legality. They can be mandamussed to

discharge their public duty, and their orders can be quashed on standard

grounds for which remedy for Judicial Review is granted (on the counts of

illegality, irrationality, procedural impropriety and also breach of proportionality).

The Central Government is interdicted by law from trespassing on the Boards'

spheres of functions.

Apropos

(i) supra: It contemplates those provinces of the Boards' functions which

are beyond the frontiers of their governing statutes. The Boards are subject

to the directions of the Central Government when they act within the confines

such provinces alone.

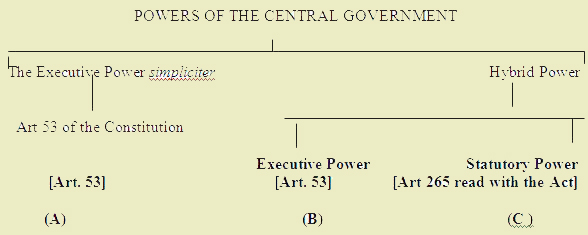

The above position reflects certain constitutional principles of fundamental importance. Without going into details, I would state them thus diagrammatically:

Explanatory comments:

(A) Governed by the Business Rules

(B) Governed by the Rules of Business and statutory bequests, if any.

(C) Powers to be exercised in accordance with the statute ONLY.

The

Revenue Department of the Government would be clear trespasser if it interferes

in (C), and their exercise of power, derived from Art. 53 of the Constitution,

would be ultra vires if done in the sphere which comes within Art.

265 of the Constitution.

CBDT

would become a creature of Direct Taxes Code Bill if enacted

The Direct Taxes Code Bill shifts the provisions pertaining to the establishment of the CBDT to this Code. The Section 116 (1) prescribes that the " Central Government shall establish, for the purposes of this Code, a Board by the name of the Central Board of Direct Taxes". Though .Section 124 .(1) puts the CBDT under duty to 'collect revenues in a fair and transparent manner' subject to the provisions of this Code, it stands excluded by Section 130 from the list of the Income-tax Authorities wherein it figures under the Income-tax Act, 1961 (vide Section 116 ). The one feature which is so pronounced is the lengthened shadow of the Central Government on the CBDT and the IRS. This phenomenon has been become so agonizing because there are good reasons to think that the Executive government most often works for the MNCs and High Net worth persons. Some lollipops offered may not drive us to get delightfully trapped in some Mephistophelean logic. Institutions are made over a long time, they can be destroyed in the flush of moments. I agree that everything is not right with the CDT and the management of the IRS. In the times we live, we have damaged all the institutions of our public life: the CBDT too has succumbed to that fate. But the right ways to solution can neither be Faustian, nor fascist, nor clandestine, nor something merely to appease. Let the Law Commission speak before we act.

CBDT would become, in the sphere of its functions, an entity subordinate to the Central Government

Section 124 of the proposed Code begins and ends with two expressions which would give sufficient leeway to the Central Government to intervene even in the statutory functions of the CBDT. These expressions are: 'Subject to the provisions of this Code' and 'perform such other functions as may be prescribed'. The amplitude of these seminal expressions can be comprehended only on taking into account the ambit of the 'Power of Central Government to issue directions" thus stated in Section 127 of the Direct Taxes Code Bill:

".(1) The Board shall, in exercise of its powers or the performance of its functions under this Code, be bound by such directions on questions of policy as the Central

Government may give in writing to it from time to time.

(2) The Board shall, as far as practicable, be given an opportunity to express its views before any direction is given under sub-section (1).

(3) The decision of the Central Government whether a question is one of policy or not shall be final."

The implications of these three sub-clauses must be understood as, if they become law, the CBDT would just be a subordinate executive agency subservient to the Central Government; and would be treated by all as one of the sub-offices of the Central Government.

(i) Apropos

Section 127(1) of the D.T.Code Bill

The semantic spectrum of the term "policy" is extremely wide and almost wholly open-ended. The Concise Oxford defines it as "prudent conduct, sagacity; course or general plan of action (to be adopted) by government, party, person etc". Black's Law Dictionary defines it as the "general principles by which a government is guided in its management of public affairs." General components of "policy", which can tell us how wide is the zone of intervention can be, have been schematically explained in Wikipedia thus:

"Policies are typically promulgated through official written documents….While such formats differ in form, policy documents usually contain certain standard components including:

++ A purpose statement , outlining why the organization is issuing the policy, and what its desired effect or outcome of the policy should be.

++ An applicability and scope statement, describing who the policy affects and which actions are impacted by the policy. The applicability and scope may expressly exclude certain people, organizations, or actions from the policy requirements. Applicability and scope is used to focus the policy on only the desired targets, and avoid unintended consequences where possible.

++An effective date which indicates when the policy comes into force. Retroactive policies are rare, but can be found.

++ A responsibilities section, indicating which parties and organizations are responsible for carrying out individual policy statements. Many policies may require the establishment of some ongoing function or action. For example, a purchasing policy might specify that a purchasing office be created to process purchase requests, and that this office would be responsible for ongoing actions. Responsibilities often include identification of any relevant oversight and/or governance structures.

++ Policy statements indicating the specific regulations, requirements, or modifications to organizational behavior that the policy is creating. Policy statements are extremely diverse depending on the organization and intent, and may take almost any form. "

The word 'policy' in Section 127 (1) is wide enough to convert group interests, even individual interests, into the policy issues. More so when Section 127(3) makes the decision of the Central Government final ' whether a question is one of policy or not. All the actions which the CBDT is prevented from taking in terms of Section 133(2) can be easily and effectively transformed into policy issues whereon directions for compliance can be issued by the Central Government to the CBDT. Besides, the Executive imperialism can wax to the point where the CBDT will have no option but to be an ever compliant instrument of this new majestic and all powerful intruder in the statutory domain of taxation.

(ii) Apropos

Section 127(2) of the D.T.Code Bill

This provision in the D.T. Code Bill is dexterously made to circle out CBDT in policy framing. This follows from the following:

(a) The Central Government would grant opportunity to the Board to express its view on 'policy' only "as far as practicable". "So far as" is a variant on the idiom 'as far as', which means "to whatever extent; as far as it etc goes, within its etc. limitations ' [ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary 1993 Edition]. "Practicable" means 'capable of being done, effected, or put into practice, with the available means; feasible: a practicable solution'. It is not possible to conceive of a situation where the Central Government can reasonably hold that it exercised power without consulting the CBDT as granting of such an opportunity is not 'practicable.

(b) The CBDT will have no option but to accept the view of the Central Government as it can avail of no remedy against arbitrary determination by the Central Government. In short, in such situations the CBDT must remaine tongue-tied as a pathetic creature.

(iii)

Apropos Section 127(3) of the D.T.Code Bill

The decision of the Central Government "whether a question is one of policy or not" shall be final. This is no more than a device to turn the Indian Revenue Service and the CBDT as the servile instruments at the disposal of what Justice Shah called in his celebrated Report on the Emergency as the "The Root of All Evil" (which is now being fathered by a nexus between the weilders of political power, and their participis criminis the non-statutory civil servants). Such provisions as those contemplated in the Code Bill remind one of Lord Atkin who said in his famous dissent in Liversidge v Anderson ( 1942) A.C. 206,at 245 :

"I

know of only one authority which might justify the suggested method of

construction. 'When I use a word' Humpty Dumpty said in rather scornful

tone, 'it means just what I chose to mean, neither more nor less'. 'The

question is,' said Alice 'Whether you can make words mean different things'.

'The question is,' said Hampty Dumpty, 'who is to be the master - that

is all."

CBDT would become, in sphere of administration, an entity subordinate to the Central Government

The Code makes, in effect, the Income-tax Department subordinate to the Central Government. And what is this 'Central Government'? As per the General Clauses Act the President of India represents the Central Government. In view of the provisions under our Constitution he is required to function in accordance with the advice of the Ministers. In exercise of the powers conferred by clause (3) of article 77 of the Constitution the President has made rules for the allocation of the business of the Government of India. Under the Allocation of Business Rules the "business of the Government of India shall be transacted in the Ministries, Departments, Secretariats and Offices specified in the rules. Under such rules all matters relating to (a) Central Board of Excise and Customs; and (b) Central Board of Direct Taxes are put under the care and management of Department of Revenue. And the Department of Revenue is headed by the Revenue Secretary, a member of the non-statutory civil service we call the IAS. In effect, under the provisions of the Direct Taxes Code Bill, if enacted, the IAS would rule. And what sort of rule that be? Read the famous Shah Commission Report how the nexus of evil between the politicians and their obliging civil servants worked during the infamous Emergency. Read the whole Report, during those locust-eaten years the IRS alone did their duty under the law with commendable boldness and perspicacity. Very recently we have seen how the Income-tax authorities in Mumbai did excellent work in exposing the misuse of the Indo-Mauritius route. They are competent and dedicated enough to achieve great tasks but they find these days the Central Government it itself an inhibiting factor. They could scale some peaks because the officers discharged the commission of duty granted to them by Parliament. In short, it is the "The Root of All Evil" that frustrates their efforts, and make the service to the nation a fruitless and agonizing drudgery..

Implications of Section 118 in the D.T. Code Bill (Delegation)

Section 118 of the D.T. Code Bill prescribes certain rules to govern the delegation of powers inter se the Chairman and the Members of the CBDT. But what is most obnoxious is 118(2 & 3) which says:

"(2) Save as otherwise provided by rules, a Member shall have the powers of general superintendence and direction of such affairs of the Board as may be assigned to him by the Central Government.

(3) The Member shall exercise all the powers and do all acts and things which may be exercised or done by that Board in respect of the work so assigned to him under sub-section (2).'

I wondered why the need was felt for the provisions which can be used even with sinister designs to make the CBDT servile and to destroy its esprit de corps . . The obliging persons can have more powers, others not obliging can simply recite the Hanuman Chalisa till they retire. How the CBDT would arrange its affairs is well settled now. A High Court has ruled long back:

"There is nothing in the Income-tax Act, 1961, nor in the Central Board of Revenue Act, 1963, which required the CBDT to act as a single body and to perform all the functions of the Board sitting together without assigning some or all of its various duties to the individual members constituting it. The words "for the purpose of regulating the transaction of business" in Section 4 of the CBR Act, 1963, are extremely wide and include in their ambit the power to make rules empowering the Chairman of the CBDT to pass an order distributing the business of the Board among himself and the member or members of the Board. (1968) 2 ITJ 69 (73) (DB)(All.)".

CBDT's circular-making power would be severly reduced and overridden under Code making tax law Draconian and unacceptable

The

powers granted to the CBDT under Section 119(2) of the Income-tax Act are

intended to be used to humanize the rigours of the law in cases which satisfy

statutory pre-conditions. As the law of Equity avoided the rigours of the

Common law, these provisions of the Income-tax Act, 1961 come to the succour

of the tax-gatherers whose claims are genuine, and who get subjected hardship

which our civilized jurisprudence does not appreciate. We do not know if

any study was made to prove that SUCH powers were exercised for ulterior

purposes. It is clear that the provisions of Section 133(2) the D.T. Code

Bill, which deprive the CBDT of powers which it has exercised over decades pro

bono publico , would surely be not justified. It also follows that by

clipping the wings of the CBDT, some administrative coterie, hand in glove

with the lobbyists of all sorts, would rule the roost through instructions

dressed in the garb of public policy directions. In the United Kingdom the

rigour of the tax law is softened by the Commissioners of by granting what

has come to be known as "the 'extra-statutory concessions to tax-payers'.

The way this is done in England has been graphically described by Hood Philips' Constitutional

and Administrative Law. "The prohibition on the suspending and

dispensing might be thought to give rise to doubts about the legality of

the practice of the Inland Revenue of making extra-statutory concessions

to tax payers. The practice is not new and certainly existed in the nineteenth

century" Judicial concern at this was voiced in Vestey v .

I.R.C. (No. 2). In R. v. I.R.C. Ex p. National Federation of Self

Employed and Small Businesses Ltd. [1980] A.C. 952 administrative commonsense

acted as the guiding principle.. Also see ("The Legality of Extra-Statutory

Concession," 180 N.L.J. 1980, 180.) The extra-statutory concessions

were granted to remove harshness, to humanize hard cases, and to conform

to commonsense. In our country the Income-tax Act, 1961 grants power to the

CBDT to remove certain hardship if the claimants satisfy conditions precedents

statutorily prescribed. Our Act, thus, clearly escapes the criticism of dispensing

power to which the British practice is subject [ Vestey v .

I.R.C. (No. 2) [1979] Ch. 177; [1980] A.C. 1148; Furniss v. Dawson [1984]

A.C. 474 ]. In short, the idea, which went into drafting Section 133(2) the

D.T. Code Bill, must be rejected.

One point more. Why should a need be felt to provide in Section 133(3) of the said Code provisions like the following:

"The income-tax authorities and all other persons employed in the execution of this Code shall observe and follow the orders, instructions, directions and circulars issued by the Board under this section."

The

law on the point has been settled by the Supreme Court in Ratan Melting's Case

(vide my article on " Ratan Melting - A landmark decision

to the extent it goes!" on www.taxindiaonline.com).

A comprehensive examination of the issues led the Hon'ble Court to declare

the following propositions of law. These are binding in terms of the Article

141 of the Constitution of India. All these propositions were essential

to the actual decision in Ratan : so they constitute the very rationes

decidendi of the Case. These propositions are stated thus:

(i) Circulars and instructions issued by the Board are no doubt binding in law on the authorities under the respective statutes, but when the Supreme Court or the High Court declares the law on the question arising for consideration, it would not be appropriate for the Court to direct that the circular should be given effect to and not the view expressed in a decision of this Court or the High Court.

(ii) So far as the clarifications/circulars issued by the Central Government and of the State Government are concerned they represent merely their understanding of the statutory provisions. They are not binding upon the court.

(iii) It is for the Court to declare what the particular provision of statute says; and it is not for the Executive.

(iv) A circular which is contrary to the statutory provisions has really no existence in law.

Conclusion

On August 17 I wrote an article in the Tribune entitled " CAG isn't a lap-dog or a hound, but a watchdog of public accounts" (also on www.taxindiaonline.com ) highlighting how that great constitutional institution was trounced by the Root of All Evil. I now feel on good grounds that if the Code Bill is enacted in the present form one more institution of great importance, CBDT. would collapse demoralizing the Indian Revenue Service as a whole. .

III

Peter Pan tinkers once again with the law of the tax treaty

The Delhi High Court held on 31 st May 2002 in Shiva Kant Jha v. Union of

India [2003-TIOL-04-HC-DEL-IT]

that the CBDT circular No. 789 was ultra

vires as in effect it subverted the Income-tax Act, and had the effect

of facilitating the gross abuse of the Indo-Mauritius Double Taxation Avoidance

Convention. This decision was reversed by the Supreme Court on 7 th Oct.2003

in Union Of India & Anr. V. Azadi Bachao Andolan & Anr (2003-TIOL-13-SC-IT) on certain ancillary reasoning on certain assumptions about its judicial

role which perception was disapproved by the Constitution Bench of the Supreme

Court in Standard Chartered Bank (2005-TIOL-79-SC-FERA-CB).

Whilst the matter was before the Supreme Court, a tax haven company became

a co-appellant in Azadi Bachao. The Government and that company

sailed in the same boat establishing an evident entente cordiale. The

lobbyists succeeded in getting Clause (a) substituted in Section 90 (1) and

sub-Section (3) inserted in the said Section by the Finance Act, 2003, and

again getting Section 90A inserted by the Finance Act 2006 into the Income-tax

Act, 1961. These provisions have been questioned before the Delhi High Court

on the constitutional grounds in the Writ Petition (C) 1357 of 2007 which

is to come up for final hearing sometime this year. Hence I do not consider

it prudent to comment on the issues involved. Strong lobbying by the vested

interests led to the substitution of Section 90 of the Income-tax Act by

the Finance (No. 2 ) Act 2009 facilitating agreements even with the specified

territories. I have already written in brief about the sinister effects of

this provision in my Legal Potpourri - 19 July 24, 2009 (India

promotes tax haven: this honking to Hong Kong ).

Now comes this Direct Taxes Code, 2009. It incorporates all the provisions referred in the above paragraph. But it proposes a revolutionary change in Section 258 dealing with 'Agreement with foreign countries'. Its last clause (8) states:

" For the purposes of determining the relationship between a provision of a treaty and this Code,-

(a) neither the treaty nor the Code shall have a preferential status by reason of its being a treaty or law; and

(b) the provision which is later in time shall prevail."

In the Writ Petition (C) 1357 of 2007 one of the core issues pertains to the determination of the relationship between a provision of a treaty and the Act. Some of the constitutional principles formulated are these:

++ That Sovereignty of the Republic of India is essentially a matter of constitutional arrangement which under our polity provides structured government, and grants power under express limitations to the organs it creates to exercise public power;

++ That the Executive does not possess any "hip-pocket" of unaccountable powers", and has no carte blanche even at the international plane;

++ That the executive act, whether within the domestic jurisdiction, or at the international plane, must conform to the constitutional provisions governing its competence ;

++ That the direct sequel to the above propositions is that the Central Government cannot enter into a treaty which, directly or indirectly, violates the Fundamental Rights and the Basic Structure of the Constitution; and if does so, that act deserves to be held domestically inoperative ;

++ That a tax treaty under the Income-tax Act is done in exercise of power under the framed in terms of Article 265 of our Constitution, not under Art. 73 of the Constitution;

++ That Section 90 of the Income-tax Act does not grant power to incorporate any sort of stipulations in a tax treaty: the province and the remit are determined by the frontiers of Section 90;

++ That no substitution or insertion can be made in Section which offends Art 265 and the constitutional principles which has begotten it;

++ That no treaty can ever go against Parliamentary enactment without its legislative consent.

++ That tax treaty in India is never placed before our Parliament, and thus is wholly an administrative act.

U.S. precedent seems to be followed by draftsmen of Direct Taxes Code, 2009

Art VI (2) of the US Constitution prescribes that 'a treaty' must be approved by the Senate by a special majority ('the two thirds of the Senators present concur'). Under the Article VI (2) of the U.S. Constitution international treaties acquire the status of a sovereign law. ' .In the United States , the Constitution provides in Article VI, cl.2 that all treaties "shall be the supreme law of the land; and the Judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding ". Under the US practice the President of United States explains to the Senate the considerations involved in framing a tax treaty. The letters of Submittal and of Transmittal pertaining to the Indo-US tax treaty are comprehensively drawn for the full information of the mind of the Senate, and through that to the whole nation. So far the relationship inter se treaties and other federal laws is concerned, relevant provisions under the US law are well-settled:

(1) If a State legislation conflicts with a treaty, the latter prevails.

(2) If a Federal legislation conflicts with a prior treaty, the legislation prevails.

(3) If a Federal legislation conflicts with a subsequent self-executing treaty,

Treaty prevails

The U.S. gives specific override on treaty terms to its laws. The Congressional enactment of the Uruguay Round Final Act provided that nothing in the Final Act could transgress the federal statutes. It is to be noted that the 123 Agreement itself gives an override not only to the US statutes, but also to other treaties having bearing on the points relevant to the subject matter in the 123 Agreement which stipulates in clear words its subservience to the domestic laws and treaties.

Bu t he US Supreme Court has upheld in Reid v. Covert (1957) the primacy of the Constitution over all treaties. Under it's the US the Executive government has no "hip-pocket" of unaccountable powers. In Hamdan v . Rumsfeld (decided on June 29, No. 05-184. 2006) the US Supreme Court said: 'Court's conclusion ultimately rests upon a single ground: Congress has not issued the Executive a "blank check."

United Kingdom position

In the United Kingdom the Tax Treaties are approved by a resolution of the House of Commons, which means, in effect, the British Parliament itself. This is the result of the Parliament Act, 1911 of the U.K. Our Constitution has incorporated similar provisions. Pointing out this aspect of the matter Keir & Lawson points out the following in their Cases of Constitutional Cases [5 th Ed p. 54]:

"Once the House of Commons had, by the Parliament Act, 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5, c. 13), secured the full and exclusive control of taxation, there was no reason why taxation should not be levied at once under the authority of a resolution of the House".

In the U.K a Tax Treaty is done through an Order in Council after a resolution is passed by Parliament, and is communicated to the Crown. The U.K and India have set up Parliamentary form of government. In the U.K. the House of Commons possesses complete control of every tax treaty though Section 788 the Income and Corporation Act 1988 authorizes the Government to enter into a tax treaty (as does Section 90 of our Income-tax Act). In the U.K a tax treaty is enacted through an Order in Council in accordance with Section 788 of the Income and Corporation Act 1988 which prescribes : "Before any Order in Council proposed to be made under this section is submitted to Her Majesty in Council, a draft of the Order shall be laid before the House of Commons, and the Order shall not be so submitted unless an Address is presented to Her Majesty by the House praying that the Order be made". Under the United Kingdom law the following two things go together:

(a) the legislative authorization under Section 788 of the Income and Corporation Act 1988 (.as does r Section 90 of our Income-tax Act; and

(b) a specific authorization of a tax treaty after the deliberations by the House of Commons ( We do not have this sort of practice in India )..

In some other countries

In Germany " a tax treaty is enacted in accordance with Art. 59 Abs. and Art 105 of the Grundgesetz (the Federal Constitution)". In Canada a tax treaty is done by enactment viz. Canada-U.S. Tax Convention Act, 1984. In Australia e very tax treaty is enacted under International Tax Agreements Act 1953. Treaty practice in different countries with different constitutional provisions materially differs. But one thing is common, They subject treaty making to an effective legislative supervision.

An inquest over proposed provisions

This proposition that "neither the treaty nor the Code shall have a preferential status by reason of its being a treaty or law" goes against our Constitution, and the rule of law. To adopt this view is to grant 'a blank check' to the Executive, more so when the tax treaties in India are not even laid before Parliament, not to say of their being passed through a resolution of Parliament.

The proposition that 'the provision which is later in time shall prevail' is also wholly misconceived. The following circumstances can be visualized:

(i) If treaty precedes legislation. In the United States the law is settled that where treaty precedes legislation, the legislation must operate.

(ii) If treaty follows legislation. In the United States the law is settled that where treaty follows legislation, it is the treaty which operates as under the US Constitution the treaties are 'the supreme law of the land'.

The adoption of the American approach would create for India numerous problems both at the international plane and in the domestic sphere: these problems are just mentioned in passing:

(a) The situation would give rise to the vexed problems which 'a treaty override' creates. Besides international pressure and persuasion will have to be courageously resisted by our Government by as the treaty partners may insist on the discharge of international obligations flowing from treaties at the international plane.

(b) In the United States where a treaty comes after legislation, it is the treaty which operates.But this is so because of some specific constitutional provisions. Under our Constitution there are no analogous provisions.

(c) In the U.K. not only there are implementing provisions in the Section 788 of the Income and Corporation Act 1988, there are specific constitutional provisions for the House of Commons to pass a resolution approving a tax treaty.

Suggestion & conclusion

I would suggest that instead of Section 258 (8) in the Direct Taxes Code, 2009, we should incorporate provisions analogous to those in the U.K. It would be most appropriate as both India and the U.K are parliamentary democracies, and the Parliamentary control of taxation is a fundamental tenet of the constitutional law of both the countries. If such changes are effected, much of the 'democratic deficit' in our treaty-making procedure would be removed. The following points are suggested (I analyze them to make my the suggestions easily comprehensible):

(a) A tax treaty is to be negotiated by the Executive Government;

(b) The tax treaty must conform to the terms of the Section 90 of the Income-tax Act;

(c ) No tax treaty should transgress the constitutional limitations which our Constitution places on all the organs it has created, to which it has granted only specifically controlled powers;

(d) The draft treaty be transmitted to the Lok Sabha for deliberation and approval within a specified period of time;

(e) The Lok Sabha would return the draft treaty bill to the Central Government to sign /ratify it as per the norms of public international law.

(f) The Central Government would be competent to re-negotiate if it thought it fit and proper; and if it does so, it must follow the normal practice of the aforesaid Parliamentary control.

|