Shivakantjha.org - PROFILE OF MY FATHER

PROFILE OF MY FATHER

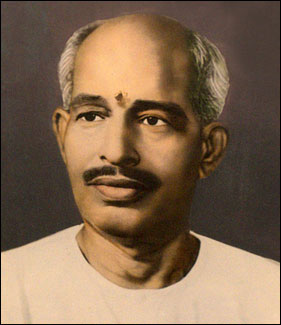

Shri Gopikant Jha

Within the surface of Time's fleeting river

Its wrinkled image lies, as then it lay

Immovably unquiet, and for ever

It trembles, but it cannot pass away.

Shelley, Ode to Liberty.

The year 1942 was a watershed in the history of India. The

new mood of vibrant nationalism had dawned on the masses. Gandhi's call had

a charismatic effect. But the ideas of Tilak and Aurobindo too contributed to

the making of the spiritual climate of the time. There was hardly any section

of society which was indifferent to the rushing waves. Students and teachers

were astir with ideas forging their new roles. Education laid stress on moral

values. Love for the motherland was considered of supreme virtue.

My father, Gopikant Jha (March 1, 1898 to June 21, 1982) was

the Headmaster of Rosera High English School at Rosera. He taught mainly English,

Mathematics, and Geography. On August 8, 1942, the All India Congress Committee,

in its Bombay session, gave a clarion call for a mass movement against the British

Raj. Father's exposition in the Matriculation class of a poem in Sir Walter

Scott's ‘The Lay of the Last Minstrel' had an electrifying effect on the young

minds of the students who were already surcharged with patriotic fervour. The

lines, which he turned into metaphors of intense patriotism, were these:

Breathes there the man, with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said?

This is my own, my native land.

His exposition inspired them. They could discover with extraordinary

verve their patriotic duties. They lived in great creative moments of our history.

Our struggle for freedom was fast reaching a decisive moment. Gandhi had touched

a chord in the common Indian masses The lines of action and thought in our national

life had met at a high point creating conditions for a great revolution. What

Macaulay had said in the course of his speech in the House of Commons on July

10, 1833 was coming true:

“ The destinies of our Indian Empire are covered with thick

darkness….It may be that the public mind of India may expand under our system

till it has outgrown that system; that by good government we may educate our

subjects into a capacity for better government; that having become instructed

in European knowledge they may, in some future age, demand European institutions.

Whether such a day will ever come. I know not. But never will I attempt to avert

or retard it. Whenever it comes, it will be the proudest day in English history”.

The students resorted to direct actions. They left their classes,

and assembled in the campus of the school. They sang in chorus, Bharatmata ki

jai and Vande Mataram. As each was acting under an inner urge, it was impossible

to say who led the inspired crowd. They showed unity and empathy seldom seen

in the era after Independence. India, for them, was Bharatmata. Bankimchandra

had written an immortal novel Anandmath in which Bharatmata was portrayed as

mother-goddess Durga. He had composed a long poem Vande Mataram (‘Hail to the

Mother'). The students had an inner urge, and an indomitable will to do all

that could be done to free their land from foreign servitude. How could they

forget that their teachers had often quoted from classical poetry that one's

motherland is much greater than even heaven?

They sang Vande Mataram in chorus, and spread out in different

directions to work against the British Empire for the cause of our nation's

freedom. Their teachers, who had seen them with thrill from the precincts of

the School, must have felt that their efforts in training them had not gone

in vain. The students and the teachers had already fallen for Gandhi's ideas,

and were ready to respond to the call made by the All India Congress Committee

for starting on mass scale a struggle for freedom which was now in its final

phase. In the morning of August 9, the main leaders of the Congress were arrested.

The Congress organization was itself declared illegal. Never in the history

of any nation had an Idea itself taken over leadership of a national struggle

for liberation. The great ideas, developed and popularised by Swami Vivekanand,

Lokmanya Tilak, Maharshi Aurobindo, Mahatma Gandhi, Muhammad Iqbal, Kazi Nazrul

Islam…..came flowering in the patriotic feats of action. The patriotic Indians

felt that as lines of thought and action had met at a high point in the nation's

life, the success was certain to come: they believed that the British Empire

in India was having only its last laugh. They got assurance in the immortal

words uttered by Samjaya in the Bhagavad-Gita :

yatra yogesvarah krsno

yatra partho dhanurdharah

tatra srir vijayo bhutir

dhruva nitir matir mama

[Wherever there is Krishna, the lord of yoga, and Partha (Arjuna),

the archer, I think, there will surely be fortune, victory, welfare and morality.]

[Dr S. Radhakrishnan's translation in his the Bhagavad-Gita XVIII.78]

Some of them, by their spontaneous actions, sent tremors disturbing

the Pax Britannica by sporadic acts of disorder which included damaging the

railway tracks and stations, and cutting of the telegraph and telephone lines.

But father felt that what shocked the British Government most was the aggressive

mood of the young India. Vande Mataram resounded everywhere. It had acquired

the status of the Veda mantra. For certain days it appeared that even the birds

and the beasts, trees and flowers seemed humming this song in the Bhairavi rag.

Its impact was electrifying, something which, father felt, brought to mind the

gongs of thalli which were sounded in the homes of the common people of Bihar

during the JP Movement which was against the Emergency which Indira Gandhi had

imposed on us. What made them extraordinary was their sturdiness of purpose,

and their dedication to the cause of the nation. They, of curse, couldn't be

oblivious to the possibilities of brutal retaliation by the savage imperial

power. Yet they embarked on their venture believing that life has been given

on the condition that the kartavya karma (Duties) must be done.

An extraversion. When father narrated what had happened on

that fateful day, he exuded cheerful serenity. But while writing about it I

feel anguished at what I see happening around us. The young of our days are

living for pelf and power alone. Now money alone matters. Higher values are

at their vanishing point. Consumerism has already taken its toll. Our cultural

tradition, and the achievements which distinguished our land from others, are

being forgotten. Now everything has a price tag. Even values have become mere

trading wares. There is a trend towards a repulsive commoditization of human

beings. It is shocking to see the slave's syndrome manifesting itself. A slave,

even on acquiring freedom, loves putting fetters on himself as a matter of own

choice. I write with an iron in my soul that this overweening lust for material

comforts at the cost of all other values has made the rich of our society a

spiritual wasteland. Swami Vivekanand was right in saying that India could expect

only from the common people as the higher sections of the society are dead from

the ethical point of view.

II

The British Government ashamed humanity by inflicting most

morbid repression on our patriotic society. Nothing is disliked by the imperialists

more than the sense of patriotism on the part of those under servitude. Patriotism

is an impregnable rampart of liberty. It is a most potent creative force in

an independent society. The Government registered its presence everywhere by

the police patrolling squad with bayonets directed to everyone in sight. Thousands

were arrested without cause. Lakhs of people suffered tribulations but now no

longer with tongue-tied patience. They were not unaware of the fact that the

cruel government could enact the Jalianwalla Bagh massacre when the troops had

fired 1,600 rounds of ammunition into the unarmed crowd of people at an enclosed

place assembled to voice their feelings against the Rowlatt Act. But even such

apprehension could not dim the people's ardour. The sweep of their pursuits

widened even to include the School, an amazing feat on the part of the students

who had been so obedient otherwise.

For a few days even after August 9, things at the school were

peaceful. But the undercurrents were strong. It reached a flash point on August

13. What happened at the School can be gathered from my father's letter to the

Sub-Divisional Officer, Samastipur who was the President and Secretary of the

School. I quote from the letter:

“I have the honour to state that yesterday some of the students

took the bunch of keys from Sonelal Sahu, school peon forcibly and locked the

class-rooms and got two locks of their own with which they locked the Headmaster's

room and the clerk's office and Teacher's Common Room. Since yesterday I have

been asking them to open the doors but they have been deferring the matter.

This day also they went on picketing and preventing the teachers and a few boys

from entering the school premises. The teachers, however, came in time and stayed

in some parts of the school premises and went back to their respective lodgings

after a few hours. I am at a loss to find what should I do in such circumstances.

This day I have found that some of the outsider also had gathered near about

the school compound”.

The revolutionaries had succeeded in disturbing the Pax Britannica.

The Sub-Divisional Officer of Samastipur was R. N. Lines I.C.S. He was tough

and had planned to strike a terror in the heart of the people. The school was

closed “for indefinite period” from Monday the August 17, 1942

Father came to know that the authorities had decided to inflict

a cruel tyranny on our people even in the villages to unnerve the common folk

drumming into their ears fear that any attempt to embarrass the British Government

would be ruinous for them. Father decided to leave for our village, Kurson.

We travelled about 50 kilometres in a bullock-cart. While travelling to our

village we ran an obvious risk of being arrested, even frayed with bullets by

the government forces.

But it was too much for the British Administration that in

the mighty British Raj an academic institution stood closed on account of the

activities of the nationalists. The District Magistrate ordered the school to

reopen with effect from August 19. Shri Rameshwar Prasad, an assistant teacher

of the School, sent a messenger to my village with a letter informing father

that the School had been reopened on the 19 th in obedience to District Magistrate's

peremptory order. Father received this letter at 9.30 a.m on August 29. He immediately

started for Rosera. What worried him most was the news that the authorities

had decided to get the ring leaders amongst the students identified so that

cruelest punishment could be inflicted on them to teach the natives lessons

never to be forgotten by them. On reaching Rosera he found the tyranny of the

British Raj at its worst. On September 5, 1942 he was summoned at the Rosera

Railway station by Najmul Huda who had been the Sub Inspector of Police. After

droning on sundries, the Police Officer shouted in hoarse and discourteous voice:

“Specify the ring leaders amongst the students”.

Father told him:

“Everyone was leading himself. It was impossible to specify

anybody.”

Father had no temptation for a reward. He could have suggested

some names to please the British Administration in order to curry favours. He

could have easily obtained the title of Rai Saheb or Rai Bahadur. It was so

easy for him to do so as he had earlier received high some appreciation from

the District Magistrate of Darbhanga who in his D.O Letter No.7928 dated June

28, 1937 had written to him:

“It has been brought to my notice that you rendered valuable

assistance in making the Last Coronation Celebration of Their Majesties a

success in your locality, and I have great pleasure in offering you my sincere

thanks for this loyal assistance and co-operation rendered by you”.

But at this time the cause of the nation was supreme. Father

stood firm. The Mephistopheles had failed. No persuasion or allurement could

work.

“So Sir you won't come out with their names. The Gandhians

come out only under the lash of distress”, said the Sub-Inspector of Police.

“Am I under arrest?” Father asked him.

The Sub-Inspector shouted, “Yes, you are. You have earned it”.

Listening this Father shouted: Vande Matram. And the Sub-Inspector

clamped hand-cuffs around his wrists. The crowd that had congregated at the

Rosera railway station shouted in chorus Vande Mataram.

Father was arrested under the Defence of India Rules, and

was produced before the Sub-Divisional Officer, Samastipur “to take his trials”.

He was admitted to the Central Jail, Patna on 13.10.42. In the chronological

Register of Convicts he was allotted number 2086. Now he became just a number!

We have read in history how the tyrants and the dictators reduced human beings

just to numbers, fitfully pullulating some concentration camps.

Father was tried under Rule 56 (I) of the Defence of India

Rules. Father was produced before an Indian most loyal to the British Government.

He was N. Huda, the Special Magistrate at Samastipur. He was known a tough man,

and was wisely feared. Tutored witnesses were produced as the witnesses for

the prosecution. They concocted stories to prove to the hilt a case against

Father. The British Government in India was panicky, and did everything to turn

the scales of justice in their favour even by hook or by crook. Father was charged

with having contravened the order of the District Magistrate under rule 56(1)

of the Defence of India Rules by holding meetings, and by taking part in processions

and thereby committed an offence punishable under rule 56(4) of the Defence

of India Rules. He pleaded not guilty to the charge. The trial was short and

swift. The judgment was on the known lines. This brings back to mind how a trial

was portrayed in Louis Caroll's Alice in Wonderland:

“Let the jury consider their verdict,” the King said, for about

the twentieth time that day.

“No, no!” said the Queen. “Sentence first - verdict afterwards.”

“Stuff and nonsense!” said Alice loudly. “The idea of having

the sentence first!”

“Hold your tongue!” said the Queen, turning purple.

The judgment of the Special Magistrate deserves to be quoted

in extenso so that the reader can have a hang of trial and punishment that a

nationalist faced when our nation's struggle for freedom was most vibrant. The

Magistrate's judgment and verdict ran thus:

“The prosecution story is that the accused who was the Head

Master of Rosera H.E.School convened Congress meetings in his school on 13 th

, 14 th and 15 th of August 1942 in contravention of the District Magistrate's

order under rule 56(1) of the Defence of India Rules. He also took active part

in Congress processions in Rosera and used and shouted “Enquilab Zindabad” “Sarkari

Raj Nash Ho” Hindustan Azad” etc. The order of the District Magistrate prohibiting

all processions and meetings under rule 56(1) of the Defence of India Rules

was duly promulgated in Rosera previously. The accused version is that he has

been all along peaceful citizen and has been discharging the duties of Head

Master to the entire satisfaction of immediate authorities and that he could

not assign any reason as to why he has been prosecuted. In support of this version,

the accused has examined Babu Harbans Narain Sinha a Zamindar of Thathia P.S

Rosera and Vice President of Rosera H.E.School. Babu Harban Narain Sinha says

“To my knowledge the accused did not take part in any meeting or procession

in the school premises”. The school was closed on 17-8-42 for indefinite period

under the advice of the Local members of the Managing Committee”. This is the

statement in his evidence in-chief. In cross examination, he says, “My house

is about two miles from Rosera. I always remained at my house during the movement.

I did not even come to Rosera”. From his statement this witness does not appear

to be quite competent to say whether the accused took part in meetings or processions

in Rosera or not, since he never went to Rosera during this movement.

I happen to be the President and Secretary of the School and

I am sure that I was not consulted even regarding the closing of School for

any period (definite or indefinite) in consequence of the student's movement.

Obviously the evidence of Babu Harbans Narain Sinha is not

of much avail to the accused. In support of his denial to have taken part in

meetings and processions D.W.2 is the teacher of Rosera H.E.School. This teacher

in one breadth stated that there was no meeting in the School compound and in

another he had to change and says that one day there was a meeting in School

compound. I am not prepared to put reliance on his statement.

Adverting to the prosecution case I find that there is the

evidence of the Sub-Inspector of Police Rosera P.S and a Havaldar of the same

P.S which clearly goes to show beyond all reasonable doubts that the accused

convened Congress meetings in School on 13 th , 14 th and 15 th of August, 1942

and also took active part in congress processions in Rosera Town shouting slogans

like “ Angrezi Raj Nas Ho, Hindustan Azad ” etc. and thus it is clear

that he contravened the order of the District Magistrate passed under rule 56(1)

of the Defence of India Rules prohibiting all meetings and processions which

was duly promulgated in Rosera Town. I therefore convict him and sentence him

to undergo R.I. for two years and to pay fine of Rs.250/- in default to undergo

R.I. for six months under rule 56(4) of the Defence of India Rules.”

No appeal had been provided against a summary conviction under

the Defence of India Rules. The Rules had been made by the government totally

panic-stricken. The World War II had cast a gloom on the British power. The

panic was so great that even their highest judiciary, the House of Lords, had

become more executive-minded than the executive in Liversidge vs. Anderson

(1942) AC. 206. The judgment by the Magistrate was shocking, more so as

no appeal had been allowed against it. Repression was so strong that we apprehended

the jail to become a concentration camp, of the sort which provided stuff to

Aleksander Solzhenitsyn in writing his Gulag Archipelago. But something for

good happened. The Calcutta High Court held that by depriving the accused of

any right to appeal the Governor-General had gone beyond his powers. Hence a

right to appeal was granted.

Father's appeal came up before J.I Blackburn, a member of the

Indian Civil Service. He was the Sessions Judge at Darbhanga. He marked most

appeals to the Indian judges who had the track-record of dismissing appeals.

But when he saw my father's Memorandum of Appeal he decided to hear it himself.

Father's advocate, Babu Chaturvuja N Chaudhary, was worried as he expected something

sinister to happen to his client as a firangi had chosen himself to decide the

case. Everyone in our village apprehended an enhancement of the sentence. It

was rumoured that most revolutionaries would face death, slow or fast, in the

prisons. But, with God's grace, a fresh breeze blew.

J.I.Blackburn had known my father when he was the S. D.O at

Samastipur. He had granted a Certificate of Appreciation to him on December

19, 1937. He asked the Public Prosecutor for the production of that certificate

which he had himself granted more than a decade back. Rejecting the plea against

the admissibility of the certificate put forth by Shri Baroda Charan, the Public

Prosecutor, the certificate was admitted on the record under the direction of

Court. J.I.Blackburn, per his judgement dated August 4, 1943 allowed the appeal

setting aside conviction and sentence of the Lower Court. This was done on the

ground that the order of the Sub-Divisional Magistrate suffered from an error

going to the jurisdiction. The findings on facts were not considered. Allowing

this appeal J.I.Blackburn said:

“It appears unnecessary to enter into the merits of the case

as there is a legal defect in the trial, in as much as the general order of

the District Magistrate constituting Courts of Special Magistrate for the

trial of particular offences was not issued until 4.10.42, whereas the learned

Magistrate in this case took up the hearing on 28.9.42 and tried the case

as a Special Magistrate and passed his orders in that capacity. The conviction

and sentence are therefore liable to be set aside. The only question however

is as to whether the case should be remanded for retrial. The accused has

already suffered R.I. for about 9 months, and in my opinion this sentence

is in any case sufficient to meet the ends of justice, especially in consideration

of the previous good character held by him.”

III

I often wondered how father could sustain himself through

his trials and tribulations which were enough to wrench any heart to the core.

He must have had a lot of apprehensions about the fate of his wife, and an infant

ailing son. But he was always unruffled as he believed that nothing could distract

him from what the duty to the nation demanded. He, like other revolutionaries,

never calculated gains and losses. They devoted themselves to achieve their

mission, to perform their kartavy-karma . I could gather later through

ample reflections that he was inspired and strengthened by the Bhagavad-Gita

as interpreted by Tilak. It had been written from November 2, 1910 to

March 30, 1911 while Tilak was undergoing sentence in the Mandalay jail in Burma

(now Myanmar). The Gita had become the very grammar of conduct of the revolutionaries.

Whether it was Tilak, Gandhi, Vinoba, Savarkar, or others not so well-known,

they all derived light and strength from the Gita. What they felt about the

Gita was well stated by Vinobaji in course of his exposition of the Gita in

the Dhulia jail in 1932:

“…My relationship with Shrimadbhagavadgita is beyond logic.

Its milk has enriched my heart and mind far more than what mother's milk had

done to my body. Reason has no play where the relationship is from the heart.

After abandoning pedestrian reasoning I keep on taking my flights, in accordance

with my capacities, in the space of the Gita. In effect I remaine in the environment

of the Gita itself. The Gita is the fundamental element of my life.” [Vinoba,

The Gita-Pravachan , First Lecture on Feb. 11, 1932]

In our society some felt erroneously that the Gita taught

Sanyasa, and whosoever read it, would become good for nothing in this world.

Perhaps, this notion developed on account of the several commentaries on the

Gita written in the medieval India by the leaders of certain sects, the main

being Samkar's (A.D. 788-820) doctrine of pure monism (advaita) holding that

the world is unreal, and wisdom and action do not go together; Ramanuja's (11

th century A.D.) Visistadvaita or qualified monism stressing exclusively on

bhakti; Madhva's (A.D. 1199-1276) dualistic (dvaita) philosophy stressing that

the prime and central path is the path of devotion; Nimbarka's (A.D. 1162) theory

of dvaitadvaita (dual-non-dual doctrine) holding the world, the soul and God

not the same though the soul and the world always dependent on God; and Vallabha's

(A.D. 1479) philosophy of suddhadvaita or pure non-dualism. They stressed on

sanyasa and bhakti, and discounted karma. Mithila drew the Gita's import from

its language itself keeping Krishna's activism, and Janak's dedication to kartavya-karma

in mind. The world-view under which such commentaries had been written had changed

in the phase our country was struggling for her freedom. This new ethos coloured

Tilak's views in writing his Gita Rahashya. The book had great influence on

father. He felt that the Gita deserved to be studied by persons of all ages,

but more so by the young people whose duty is to act. He used to refer with

delight what Tilak had himself written in the Introduction to his book: to quote

--

“Without acting nothing happens. You have just to go on

doing your duties with detachment. The Gita had not been said for those fatigued

by running their affairs with crash selfishness reading the Gita merely while

away their moments. The Gita was not said for those preparing to retire from

the World.”

[Translated by me.]

The great commentators failed to consider the fact that the

Gita is a sound grammar of revolution. Lord Krishna was Himself a great revolutionary

who stood against all injustice and arbitrariness. He inspired the revolutionaries

as Christ had inspired the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, headed

by Martin Luther King, which conducted non-violent revolution in America to

achieve civil rights.

Many of the nationalists enjoyed their prison terms, long

or short, with sublime fortitude. They had sufficient time for an inner odyssey

absorbed in the rainbow of their inner space. They had learnt from their tradition

an idea that even when one is driven on own self in acute loneliness, one is

not without the company of God.

Father had great admiration for the V.D. Sawarkar. When I was

writing a paper on 1857 to mark the centenary celebration of that great event,

father advised me to read Sawarkar's History of the War of Indian Independence.

Sawarkar was of the view that the great event of 1857 was, in effect, the First

War of Indian Independence. It had been powered by the conjoint forces of Swadharm

and Swarajya . The book impressed me most. I was glad that my

essay was adjudged the best by the Committee of Evaluators consisting of Dr

Sital Prasad Sinha, Pundit Nageshwar Mishra, and Dr Sachhinath Mishra.

It was a unique experience to stand gazing at Sawarkar's portrait

in the cell on the second floor of the National Memorial Cellular Jail at Andaman.

In 1998 I visited this cell in which the great man had spent his confinement

for than a decade from July 4, 1911 undergoing imprisonment for fifty years!

I stood spell-bound before his portrait. I read the beautiful prayer that he

had composed. While in the jail his day began at 5 a.m. chopping trees with

a heavy wooden mallet. Often he was yoked to the oil mill. I was told by my

guide that he had to hear the last wailings at the gallows which were just down

his cell. It was amazing that he kept his mental balance despite his years of

acute drudgery. Only great faith in himself, and in Lord Krishna's dictum -

Na me bhaktah pranasyati my devotee never perishes)-- must have saved him from

being withered in such excruciating of circumstances. Whilst leaving that cell

I was struck by the sight of a luxuriant ancient Peepal tree inside the campus

coming within the full view from the cell. He must have spent much of his time

observing the tree. The Gita says that amongst the trees Krishna is this tree.

He must have read the Gita on the leaves of the tree, he must have heard Krishna's

flute in the flutter of the twigs, in the twitters of the birds with which the

tree abounded. Sawarkar and those like him could not have done what they did

without believing in what the Gita says:

Uddhared atmana ‘ tmanam

na ‘ tmanam avasadayet

atmai ‘ va hy atmano bandhur

atmai ‘ va ripur atmanah

[Let a man lift himself by himself and let him not degrade

himself. For thy Soul alone can be thy friend, and thy Soul can be thine enemy.]

Father was in the Bankipore jail while undergoing his sentence.

He bore with fortitude the troubles he faced without grumbling or repentance.

He, like others of his sort, believed in what Richard Lovelace had said in the

oft-quoted lines:

Stones walls do not a prison make

Nor iron bars a cage;

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an hermitage.

How difficult it is for many of us to understand these great

men as now live in a society in which Bharatmata is painted naked, when Gandhi

is sketched on sandals, when Prophet Muhammad is turned into a ‘cartoon'. Sometime

back there was a furore raised by fakers about the propriety of the presence

of Swarkar's painting in the cell. Our much-vaunted civilization is shaping

systems which run on the craft of deception, and the strategy of corruption.

The sensibility to be thrilled by the ideas of swadharma and swaraj

is waning fast.

Savarkar's photograph in a cell in the

cellular jail, Andamans

On being released from the jail he came straight to his village.

His homecoming was sudden. We did not know anything about it. We saw his silhouette

in the moonlit night on the road that bypassed the cremation ground where we

had gone, at midnight, to cremate my grandfather who had died in his nineties.

He was proud of his son. At that time I was only of 5. I saw my grandfather's

last smile before his death. He slowly hummed Shri Krishna Govind Hare Murare,

He Nath Narayan Vasudeva, and then was no more. Father could reach in time.

He could offer on the funeral pyre five dried mango twigs as his obeisance.

For us joy and sorrow were yoked together. It was a chiaroscuro in the cremation

ground.

IV

Father was essentially an educationist. He began his career

as a substitute teacher in December 1924 at C.M.S. High School, Bhagalpur. Immediately

thereafter he went to Rosera to establish a High School at the request of the

people of that place. But after a short period there, he shifted to Barh to

become an Assistant Teacher at Bailey School and later its Assistant Headmaster

till sometime in 1929. He again went back to Rosera where he worked as the Headmaster

of the High English School from 1929 to his arrest in 1942. After his release

from jail on June 22, 1943 he joined the post of the Headmaster of M.C.H.E School,

Kadirabad at Darbhanga where he worked till May 31, 1965 when he retired. In

the post-retirement phase he remained associated with the Darbhanga Public School

till my mother's death on December 9, 1973 on which date he entered the phase

of Sannyasa.

As he was essentially an academician, it is worthwhile to focus

on his ideas which conditioned his teaching over more than fifty years. He had

a coherent and integrated philosophy of education. The scope of this chapter

does not permit discussion its in detail. But some core ideas deserve to be

highlighted. His ideas about the objectives of education were the same as stated

by Lin Yutang in The Importance of Living:

‘The aim of education or culture is merely the development

of good taste in knowledge and good form in conduct. The cultured man or the

ideal educated man is not necessarily one who is well-read or learned, but

one who likes and dislikes the right things. To know what to love and what

to hate is to have taste in knowledge. Nothing is more exasperating than to

meet a person at a party whose mind is crammed full with historical dates

and figures and who is extremely well posted in current affairs in Russia

or Czechoslovakia, but whose attitude to point of view is all wrong.'

He was worried by the growing indifference of the students

towards the finer creations of mind. Education is meant to develop the students'

courage, and their faculty of imagination as without these good character cannot

be built. The worst problem which humanity is facing now is what is known as

the Wallace paradox (stressed by the great Alfred Russel Warren) which refers

to our present plight illustrated by the exponential growth of technology matched

by the stagnant morality. There are good reasons to believe that without moral

imagination man and science would perish together. Character is destiny. He

would often refer to what Herbert Spencer said about education; ‘Education has

for its objects the formation of character”. History shows itself more and more

a race between education and catastrophe. But the Gandhian message has been

overlooked in our Free India which is now imperilled by crash egocentricity

and rabid corruption.

He derived his technique of imparting education from the Bhagavadgita

itself. He suggested to the students that a difficult subject is studied best

when it is studied with concentration again and again. This is the abhyasayoga

of the Gita. His technique was participative; the students felt at home to put

questions to grasp the issues better. He could distil out what was the best

in his students. Didn't Shakespeare say: There is some soul of goodness in things

evil, Would men observingly distil it out.

He was a perfectionist. He would never condone linguistic

lapses. Like H.W. Fowler, whose Dictionary of Modern English Usage he frequently

consulted, he was an instinctive grammatical moralizer. He had purchased a battery

set of Phillips radio in 1954 so that I could regularly hear the BBC broadcast

for acquiring a better sense of English language, and for improving general

knowledge. He had a special liking for the Times Literary Supplement which he

was getting direct from the United Kingdom. The editorial note of August 2,

1957 had commented on Fowler:

“A moralizer no doubt he was; but he has no categorical imperatives.

His morality is purely teleological, and the end to which it is directed can

be reduced to a single idea : lucidity.”

Same could be said of my father.

His educational philosophy was wholly Gandhian. He emphasised

on moral instruction, and vocational training as the essential ingredients of

education. Once he had explained the symbolic relevance of the Spinning Wheel

on which we worked every day those days. Gandhi felt that the Spinning Wheel

would create centres of creativity in every household. This would enable our

society to develop creativity and discipline in every household. A Spinning

Wheel would have become a symbol of creative growth. Working on the spinning

wheel could develop power of concentration, and provide moments to tranquilise

one's system so that nobler values could be pursued. If the model of Gandhian

education would have been implemented, every household would have become centres

of creativity. Of course, if this would have happened, our degenerate politicians

of our days wouldn't have obtained the herds of the slogan shouting hoodlums

to promote their interests. Father shared the concern which had been voiced

by the great scientist Alfred Russel Wallace in Bad Times as far back as 1885:

“We thus see that the evils under which we have suffered,

and are still suffering, are due to no recondite causes, to no laws of inevitable

fluctuation of trade, but wholly to our own acts and to those of other civilised

nations. Whenever we depart from the great principles of truth and honesty,

of equal freedom and justice to all men whether in our relations with other

states, or in our dealings with our fellow-men, the evil that we do surely

comes back to us, and the suffering and poverty and crime of which we are

the direct or indirect causes, help to impoverish ourselves. It is, then,

by applying the teachings of a higher morality to our commerce and manufactures,

to our laws and customs, and to our dealings with all other nationalities,

that we shall find the only effective and permanent remedy for Depression

of Trade.”

He always believed that the culture of Guru Shishaya parampara

should be cultivated in our educational system. As a teacher he maintained

very close contact with students. He took a lot of interest in the welfare of

his students. His students could come to him for learning, and for receiving

good counselling whenever they needed that. He was a loving teacher. No barrier

of formality separated him from his students.

V

Like most of the Indians my father was astik. An astik believes

in the Vedas, and reposes faith in God. One who believes in positive values

of existence is an astik. The etymology of astik (from Asti) is suggestive:

it refers to existence itself. He did not consider Bertrand Russell an atheist

as he had not ceased to have an indomitable quest for knowledge, and had had

profound interest to improve the conditions of human beings in these locust-eaten

years of ours. Father was syncretic in his religious ideas. He bore on his forehead

a bright vermilion mark. Over it three flourishing lines of the holy paste of

ash were drawn. These subdued grey coloured lines, so exquisitely drawn with

the finger-waves, indicated faith in Shiva. The vermilion mark expressed faith

in Shakti. The lines flanking closely the red mark and moving upwards vertically

on the forehead expressed his faith in Vishnu. Father strictly followed the

norms of the ashrams. His infinite trust in God helped him to get over life's

ennui; and enabled him to receive death as his final prostration on Lord Krishna's

lotus-feet. Life, he believed, is a mere sparrow's flight from the unknown to

the unknown with a temporary perching on the wooden beam of a room with windows

open, and the doors ajar.

Those days most students had a dharmic bent of mind in pursuing

their studies. This helped them improve their power of concentration, and made

them more focussed. It was customary to register a reverential bow to the book

or the pen when picked up from the ground if it ever fell down. When our feet

unwittingly touched a book we considered it a sacrilege. Every year Sraswati

was worshipped at most schools. She is the goddess of learning. The worship

of Saraswati is celebrated even now, perhaps more, but the bent of mind in doing

so is no longer that. It has become more a fun. The culture of our fast growing

acquisitive society has taken its toll. For father deeds are important but what

is more important is the state mind in doing things.

He believed that the greatest hazard to our technology-led

society is the stagnant morality and overweening hubris. He shared the ideas

of Alfred Russel Wallace whose The Wonderful Century: Its Successes and

Failures came out 1898, the year of his birth. Our great scientific advancements

constitute the beginning of a new era in human progress. But is only one side

of the shield. ‘Along with these marvellous Successes --- perhaps in consequence

of them ---there have been equally striking Failures, some intellectual, but

for the most part moral and social.' Corrective measures must be taken before

it is too late. Our society needs values which can lead to general welfare of

people, and create better capacity for reasonable prognostication. Life is not

to decay: ‘Like corpses in a charnel'. These words of Shelley in Adonais come

to mind:

The One remains, the many change and pass;

Heave'ns light forever shines, Earth's shadows fly;

Life like a dome of many coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.

VI

Father practiced the precept of ‘simple living and high thinking'

all through his life. He was all against the consumerist culture under which

the vested interests generate even non-essential needs. If one wants to maintain

dignity, the best way is to control one's needs. He provided us a talisman which

can stand in good stead while moving through the markets. This talisman is most

essential in our consumerist society. Whenever a desire springs up for things

on sale, it is prudent to ask oneself: ‘Is it essential for me? Can't I do without

it?' He believed that our resources are limited, and, hence, they must be used

without profligacy. He always stressed on the quality of his life. Joys didn't

elate him. He bore sufferings with tongue-tied patience. He was always happy

with whatever his life brought to him as his share. He lived in moments available

to him; he never fretted about unborn to-morrow or the dead yesterday. He followed

Gandhiji's instructions in the matter of food habits. When I visited Gandhi's

Wardha Ashram I found similar norms written on the board on display in the campus.

He was sad at the governmental indifference to Gandhi's ideas despite the fact

that they alone can save us from our present-day jeopardy. For him life provides

an opportunity to live with delight. One should make one's life a virtual festival

of colours. Kabir expresses in these famous lines:

Jeevan ke dina chaar,

Holi khel mana re

[Life's spring last not long O mind ! Enjoy the colours of

festive delight]

In the ups and downs of his life my mother was his great companion

and an unfailing source of inspiration. I have written about her in a separate

chapter. Every devotee of Shakti prays to the Deity;

Grant me this wish, O Mother Supreme, That I may be blessed with

a wife whose ways accord well with my heart, And who can enchant my mind,

And can help crossing the most difficult ocean of life

And one who comes from a good family.

--(Translation mine from Argalastrotram).

Goddess surely fulfilled my father's wish. Theirs was a rarest

of rare cases when the husband and the wife were so truly made for each other.

VII

After his release from jail, he enjoyed for some time a cathartic

experience in his village. But his heart's desire was still education. It was

difficult for him to get a job. Who would employ one who had gone against the

British Empire? It was just a chance that he met a band of patriotic persons

who needed him to function as the Head Master of the M.C.H.E School situated

in a backward area of Darbhanga. Teaching again became his dominant concern

and chief delight. He had never been a politician; he never intended to dabble

into politics. He was a through patriotic person who was wholly at peace with

himself by imparting education to the young children of the poor. Michelangelo

sculpted the Pieta for St Peter's from marble: he drew out from the stone the

sublime beauty which lay in the stone. A teacher's job resembles the sculptor's

craft as he too discovers things of value in his students, and helps them to

manifest their inner worth. For a good teacher his students form his vidysvamsa,

become members of a family.

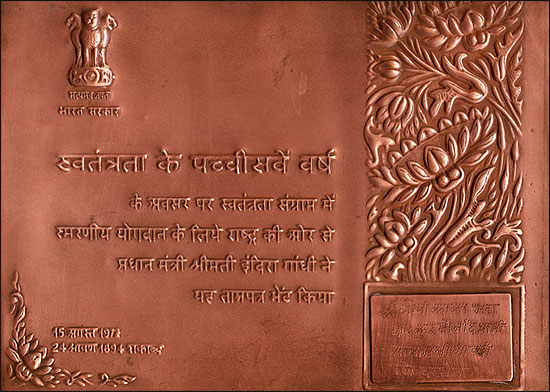

In appreciation of my father's contribution to the struggle

for India's freedom, Prime Minister Mrs. Indira Gandhi presented to him, on

August 15, 1972, a Tamrapatra on behalf of the Nation on the occasion of the

Twenty fifth year of India's Independence. He considered this appreciation his

greatest asset. For me it is the most valuable heirloom. Our nation granted

him a pension of Rupees 200/- a month from August 15, 1972. He never needed

anybody's financial help till his death in 1982.

Father was disturbed by the Declaration of Emergency made by

Mrs. Indira Gandhi on June 26, 1975. He was shocked to find that the Emergency

was declared on flimsy grounds; and the Constitution which our people had given

to themselves was subverted purely for personal reasons. He agreed with many

who considered the ignominious Emergency a darkest chapter in the democratic

history of India. He expressed himself against the Emergency though his failing

health did not permit him to take up an active role in opposing it effectively.

He was certain that her dictatorship was bound to end as the grain of our society

did not permit any tyranny for long. The greatest assurance against a tyranny

is the world-view of the common people. He was amazed that she missed the wisdom

born of history. Her father had done so much to tell her about history, both

of India and the World, but, perhaps, it went all in vain. This bears out Georg

Wilhelm Hegel who said:

“What experience and history teach is this --- that people and government

never have learnt anything from history, or acted on principles deduced from

it.”

He was glad when the sordid phase of the Emergency came to an end. No less

shocking was the decision of our Supreme Court upholding the morbid Emergency.

During the Emergency our Supreme Court had buckled, but most of the High Courts

had stood erect protecting people's rights. The Calcutta High Court was one

of those which did not let our people down even in those darkest hours. When

I was enrolled as an Advocate by the Calcutta Bar Council, father was overjoyed:

he was proud of me. This High Court had declared in 1942 the Viceroy's order

under the Defence of India Rules ultra vires his power. The Viceroy had not

granted right to appeal to the accused. The quashing of this order facilitated

my father to prefer an appeal. About this I have already written. That judgment

of the Supreme Court shocked him. Even when the end of the British Empire appeared

just round the corner in 1942, the Calcutta High Court stood erect; but it was

quite amazing that a mere whirl of the Emergency swept our Supreme Court off

its path. But he was an optimist; he felt that even this dark hour would pass.

Of course, he had a tragic optimism.

VIII

In this chapter I have put some spotlights on my father's personality,

and have reflected on some of his ideas which appear to me valuable even now.

Goethe said:

At the whirring loom of Time unawed

I work the living mantle of God.

I feel it apt to conclude this Chapter with lines variating

on Goethe's:

At the whirring loom of Time unawed

He worked the living mantle of God. [Goethe in his Faust (R. Anstell's

Translation quoted by Arnold J. Toynbee in A Study of History Pg.632)]

EXTRACTS FROM A DIARY OF A FREEDOM-FIGHTER

Father recorded a graphic account of his involvement in the

Quit India Movement and all that followed as its sequel. As this account comes

from the Freedom Fighter's pen it has a special sanctity and value. I quote

a portion of what he had written:

“August 9, 1942 was a great day. The news that the leaders

of the Congress Party were arrested by the then British Government en block

alarmed the Indians. On the proclamation of “Quit India Movement“ there was

a massive agitation throughout the country. My students at Rosera H.E.School,

whom I had ever taught the lesson of patriotism while teaching patriotic songs

in Matriculation Classes, could not check their patriotic impulse. They went

on strike and marched in a procession shouting “Inqulab Jindabad” and “Angrejon

Bharat Chhoro.” They were joined by the Bazar and village people. They all marched

to the Government offices to paralyse Government work. They held meetings where

slogans were shouted and speeches were made. The school had to be closed. Government

work everywhere got paralysed. There was wide-spread repression. Many persons

were arrested and some even shot at. Houses were burnt; properties were confiscated;

and many kinds of unheard-of tortures were inflicted on people. Such repressive

measures had never been imagined in civilised countries. Four teachers - namely

Ramakant Jha, Kuldeep Mishra, Janardhan Jha and Rameshwar Prasad - were arrested

on 2 nd September, 1942 and were sent to the Police Station and thence to Samastipur

Jail. Nazamul Hoda was the S.I. of Police Rosera. He arrested many innocent

persons and made huge amount of money as illegal gratification. It was not the

time of thinking how to save oneself from the police clutches.

I was also arrested on 5 th September, 1942 at the Rosera

Station by the Inspector and the S.I. of Police. I could not be freed even for

a moment. Fortunately my wife and my son, who was a child then, were at Kurson,

my village. On arrest I was sent to the Samastipur lock-up in Jail to stand

a trial in future on the submission of the police report. I was brought to Samastipur

Jail where my other companions were placed. After about a month the S.D.O tried

me convicted me and sentenced me to undergo R.I. for 2 years. I was to pay a

fine of Rs.250 in default R.I. for 6 months.”

Reflections on an ideal teacher by one of his students: “Remembering

Gopi Babu” by Prof. (Dr ) Bishwanath Prasad, M.A.,M.D.PA., Ph. D, M.P.A.

(USA), etc, former Vice-Chancellor of Magadh University & former Principal,

Magadh University

"Late Sri Gopi Kant Jha embodied the qualities of an ideal

teacher and of a successful administrator of a higher secondary school in a

backward district of North Bihar in the forties of the twentieth century. He

ranked high amongst good teachers of English literature. He was endowed with

competence of elevating the level of discourse from one of information to that

of knowledge, to that of wisdom as and when occasion so demanded. Equipped with

soft power of his noble ideas and values, he could forge a lasting relationship

with some of his acquaintances through working for a shared purpose and goal.

In exercising self-discipline of an authentic and compassionate guide, he made

values become consistent actions. Excellence in education was not an act for

him but a habit. He was a perfectionist, a doer always willing to put an extra

effort, and resources for his institutional strengthening endeavour. He was

a disciplinarian and upholder of moral integrity on the school campus. He well

looked after the institutional tasks, be they concerned with selection of faculty

staff, purchase of library books, or books meant to be awarded to rank holders

of the classes. His performance for an aggressive recruitment of faculty member

was directed at getting teachers of positive attitudes to teaching. His effort

stands corroborated by this writer’s perceptive observance …. He

succeeded in galvanizing a generation of youth during the freedom movement period

enjoying the reward of satisfaction of a job well done striking a balance between

the demands of career development and character building. His discernible contributions

to the consolidation of secondary educational system will surely endure, and

so also his memory."

|